Prophecies of the end of the world in 2012 are based on a misreading of the Mayan calendar. This is pointed out in Robert Bolton's excellent study of the cycles and philosophy of time, The Order of the Ages. Himself a Catholic Neoplatonist, Dr Bolton examines the various calendrical systems and prophecies of different ancient civilizations, finding a number of significant convergences, indicating the possible end of a cycle of history (NOT "the end of the world") towards the end of the present century. The Mayan calculation is complicated, but if Dr Bolton is right we should take the Mayan "year" of 360 days as a symbolic round number. The Mayans were as aware as anyone of the fact that a solar year was a few days longer than this, and if this fact is taken into account the end of the present cycle would come around 2087, according to their calendar.

Of course, this kind of speculation will not convince or even interest most people, but some would like to go further and explore the prophecies of the Book of Revelation, comparing these to the messages of the various apparitions and visionaries approved by the Church (Fatima, La Salette, and so on). For those readers, Emmett O'Regan's book Unveiling the Apocalypse will be a delight. In it he even goes in some depth into the ancient number symbolism of the Bible, called Gematria. His website (follow the link I just gave) gives further material and offers a sample chapter of the book. Some of these topics, such as Gematria, also come into my book All Things Made New, although unlike O'Regan in my "spiritual" interpretation of the Apocalypse I don't refer to extra-scriptural prophecies and I don't come to conclusions that relate to specific dates and historical events.

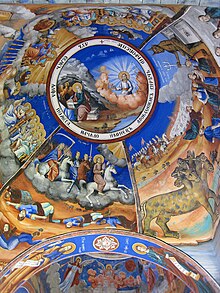

Illustration: Fresco from Osogovo Monastery, Macedonia (Wikimedia Commons)

Saturday, 31 December 2011

Tuesday, 27 December 2011

A mystic in New York

|

| "Remember" |

Saturday, 24 December 2011

What's in a landscape?

In a previous post some time ago I mentioned G.K. Chesterton's aversion to impressionism, with which I did not quite agree. I want to look now at some landscape art that I find particularly inspiring, both to recommend it to your attention and to investigate a little for my own sake why I find it so appealing. I begin with a group of artists known as THE GROUP OF SEVEN or Algonquin School, whose work is being exhibited at the Dulwich Picture Gallery until 8 January. Unfortunately I will miss the exhibition, but do go if you can. The artists in this group were born or lived in Canada from the end of the

Wednesday, 21 December 2011

Social network

Billed as the "social network of the JP2 and B16 generations", Ignitum Today seems well worth a visit.

Thursday, 15 December 2011

Weaver on Education

A superb essay by Richard M. Weaver is featured by "The Imaginative Conservative", one of the blogs I recommend. Please read it if you have the time.

Monday, 12 December 2011

Faith formation

Some readers might not be aware that I am currently working on two other blogs, which explains why postings are a bit slow on this one for the time being. One of them is on Catholic social teaching (The Economy Project). The other is about the Christian mysteries (All Things Made New), and currently features a series on the revival of "mystagogy", or faith formation through the study of symbolism and sacraments and liturgy.

Tuesday, 6 December 2011

A tribute to John Paul II

Friday, 2 December 2011

Nature full of grace

For reasons of space, the following had to be omitted from our recent "Gardens" issue of Second Spring. Meanwhile readers who enjoyed that issue may like Jane Mossendew's blog Gardening with God.

An Early Kalendar of English Flowers

The Snowdrop in purest white arraie

First rears her hedde on Candlemas daie;

While the Crocus hastens to the shrine

Of Primrose lone on St Valentine.

Then comes the Daffodil beside

Our Ladye’s Smock at our Ladye-tide.

Aboute St George, when blue is worn,

The blue Harebells the fields adorn;

Against the day of Holie Cross,

The Crowfoot gilds the flowerie grasse.

An Early Kalendar of English Flowers

The Snowdrop in purest white arraie

First rears her hedde on Candlemas daie;

While the Crocus hastens to the shrine

Of Primrose lone on St Valentine.

Then comes the Daffodil beside

Our Ladye’s Smock at our Ladye-tide.

Aboute St George, when blue is worn,

The blue Harebells the fields adorn;

Against the day of Holie Cross,

The Crowfoot gilds the flowerie grasse.

Wednesday, 23 November 2011

What's wrong with modernist architecture?

An interview with Nikos Salingaros, a follower of Christopher Alexander, on what went wrong with architecture in the twentieth century. "By contradicting traditional evolved geometries, modernist and contemporary architecture and urban planning go against the natural order of things. When an architect or planner ignores the need for adaptation and imposes his or her will, the result is an absurd form—an act of defiance toward any higher sense of natural order. There is no room for God in totalitarian design." From The Public Discourse, with a link to download the full interview. For wonderful articles on Christian architecture, see the Institute for Sacred Architecture web site.

Wednesday, 16 November 2011

The coming of THE CHILD

Humanum has a particular concern with issues that directly affect the poor and the vulnerable in our society. Each issue will have a main theme around which the reviews and articles cluster, and we begin with an issue on THE CHILD, because this reveals the foundation of our perspective on humanity: the child is the purest revelation of man and his relationship to Being. The lead article is a major piece by the Editor of Communio, Prof. David L. Schindler, which goes right to the heart of our present cultural malaise.

The Humanum website was designed by Adam Solove. For an article about the first issue, go here.

Friday, 4 November 2011

Discussion of The Lord of the Rings

What follows is a hitherto unpublished discussion of The Lord of the Rings by Gregory Glazov and Stratford Caldecott. (And if Tolkien interests you, you might also like to take a look at Andrew Abela's article "Shire Economics".)

Thursday, 29 September 2011

Second Spring Catechesis

Take a look inside, and help your child follow along with the new Missal translation!

Some years ago we started our own publishing with the idea of producing high-quality artwork in children's colouring books in service of an imaginative and symbolic approach to catechesis. That simply means that rather than talk to kids about religious ideas, we would show them. Our colouring books use the symbolic language of Nature and the Bible to introduce children to the mysteries of the Catholic faith. One of our books is written by Scott Hahn. The beauty and enjoyment of interacting with the illustrations means that the child enters more deeply into the symbolism and the "visual language" of faith - the same language we find in icons, illuminated manuscripts, stained glass windows, mosaics, and frescoes.

In developing this approach, Leonie Caldecott was partly inspired by Sophia Cavaletti. Leonie saw it as an application of the fundamental principle of the new evangelization: the intimate association of truth and goodness with beauty. This implies a vital role not only for intelligence and will but for imagination in religious formation. The Vatican has called for an “evangelization through beauty”, since this is the main way in which modern people can still relate to the Christian tradition and begin to grasp its meaning for them. But the first challenge was getting children to relate to the central act of worship, the Mass, which is why our lead title was always THE MASS ILLUSTRATED FOR CHILDREN, now issued in a revised edition, with improved illustrations and a text drawn from the new translation of the Roman Missal - so that the book can be used not only for colouring but as a first Missal, helpfully guiding the child through the unfamiliar prayers and responses of the Mass. (Order now, for delivery in October.)

Second Spring Catechesis involves taking the child, and the child’s sensibility and culture, much more seriously than most other forms of catechesis have done. It opens windows in the child’s imagination through which the vision of the faith can be transmitted, or (to vary the metaphor) it prepares the ground and plants the seeds for a later, more intellectual appreciation of the faith in the child’s mind. To nourish the child’s sense of mystery and of the sacred is essential for the healthy development of the life of faith and prayer through the difficult years of adolescence that lie ahead. The further benefit of exposing children at an early age to a wide range of rich and beautiful imagery lies in helping to perpetuate the best artistic traditions of Christianity. By fostering an appreciation of how icons function to express religious truths and support the interior life, Second Spring Catechesis thus complements and extends the work being done for an older age group by David Clayton in Thomas More College’s “Education in Beauty” program. Indeed David himself has illustrated two of our books for children, adapting his knowledge of traditional styles and techniques for the purpose. New titles are in preparation for next year, but in the meantime we hope you will order THE MASS for your parish or class, either through our UK distributor Prompt Reply, or if you live in N. America through our US distributor, Thomas More College, who can also give you current US prices.

Some years ago we started our own publishing with the idea of producing high-quality artwork in children's colouring books in service of an imaginative and symbolic approach to catechesis. That simply means that rather than talk to kids about religious ideas, we would show them. Our colouring books use the symbolic language of Nature and the Bible to introduce children to the mysteries of the Catholic faith. One of our books is written by Scott Hahn. The beauty and enjoyment of interacting with the illustrations means that the child enters more deeply into the symbolism and the "visual language" of faith - the same language we find in icons, illuminated manuscripts, stained glass windows, mosaics, and frescoes.

In developing this approach, Leonie Caldecott was partly inspired by Sophia Cavaletti. Leonie saw it as an application of the fundamental principle of the new evangelization: the intimate association of truth and goodness with beauty. This implies a vital role not only for intelligence and will but for imagination in religious formation. The Vatican has called for an “evangelization through beauty”, since this is the main way in which modern people can still relate to the Christian tradition and begin to grasp its meaning for them. But the first challenge was getting children to relate to the central act of worship, the Mass, which is why our lead title was always THE MASS ILLUSTRATED FOR CHILDREN, now issued in a revised edition, with improved illustrations and a text drawn from the new translation of the Roman Missal - so that the book can be used not only for colouring but as a first Missal, helpfully guiding the child through the unfamiliar prayers and responses of the Mass. (Order now, for delivery in October.)

Wednesday, 28 September 2011

"I See All"

Consisting of around 100,000 little black and white pictures with captions, interspersed with many gorgeous full-colour themed pages like this one, I See All (click on title for link) was billed as the "world's first pictorial encyclopedia" when it started appearing as a part-work in 1900, edited by Arthur Mee. Like the more recent Look and Learn, which I wrote about earlier, it is available online or in ebook format. My family inherited a set of the bound volumes, and I remember poring over it as a child. The imagination of a child invests such things with an intensity of life and colour - and an "atmosphere" - that grown-ups have mostly forgotten, until perhaps they chance on an old comic book or encyclopedia and experience a wave of nostalgia. We learn more from these experiences of beauty than we can put into words. I will be featuring some of the colour pages from this publication in future posts. They may be useful or inspirational to someone.

Tuesday, 20 September 2011

Purpose of education

At the end of Part Four of G.K. Chesterton's What's Wrong with the World comes this wonderful quote, which is worth pondering:

There was a time when you and I and all of us were all very close to God; so that even now the colour of a pebble (or a paint), the smell of a flower (or a firework), comes to our hearts with a kind of authority and certainty; as if they were fragments of a muddled message, or features of a forgotten face. To pour that fiery simplicity upon the whole of life is the only real aim of education...I take this out of its context, where he is talking about female education in particular, to encourage you to go to the original. The passage ends with the famous motto: "if a thing is worth doing, it is worth doing badly".

Wednesday, 7 September 2011

Heraldry

One way into a study of medieval history for some children is the aesthetic pleasure of heraldry - an imaginative delight in the visual symbolic language employed by feudal knights to distinguish themselves in battles and tournaments. The Church still has her own elaborate system of ecclesiastical heraldry, devising formal emblems for bishops and popes. Another angle would be especially appropriate for families reading Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings. Not only did Tolkien develop several viable languages for his "secondary world", including varieties of Elvish, but he even devised a series of mandala-like heraldic emblems for the different Elvish houses - you can find them online here or here. Some children will be fascinated with these, and they could be used in many different ways by homeschoolers (as I suggested in a previous post). For example, you could explore the symbolism of shapes and colours and how these relate to the story, or you could make black and white versions to colour in, or you could invent new ones (for example make a heraldic emblem for your own family or those of your friends). This in turn could lead you to compare Tolkien's symbology with traditional European heraldry. The subject also opens the door to possible discussions of symbolism in general, and of tradition, and of chivalry. You might like to read Chesterton on "pictorial symbols" in his book The Defendant, the chapter on Heraldry, or passages in his novel The Napoleon of Notting Hill where he talks about the "ancient sanctity of colours" and at the end of The Man Who Was Thursday where the six protagonists are clothed in symbolic vestments representing the days of creation... Then again, there is the whole subject of chivalry, that code of male ethics with which the Church tried to channel the aggression of feudal Europe in a more spiritual direction - but that calls for a separate post.

Friday, 19 August 2011

A Little Way

I have written previously about a radical form of homeschooling called "unschooling". Perhaps the best introduction to unschooling for Catholics is a book edited by Suzie Andres, which I had previously seen in draft. Now published under the title A Little Way of Homeschooling, it is based on the experiences of a group of home-schooling families who saw in John Holt the articulation not just of a theory but of a spirituality of education, akin to the “Little Way” of St Thérèse of Lisieux – a way of trust and simplicity. Being based on the actual experiences of families over many years, the book builds a certain confidence that unschooling is not merely an ideology, and need not be considered an impractical, idealistic dream. (I should mention also the delightful black and white line drawings.)

These parents know exactly what they are doing. Here is Karen Edmisten: "Most of us would probably agree that in many areas of our society specialization can and does lead to fragmentation. Parsing education into subjects, which are then studied in a vacuum apart from other subjects, can also lead to a fragmented understanding of both the subjects and the world around us." Contrast the method or "unmethod" described in action here, in which history is full of literature, literature marches through history, history is interlaced with science, and everything points to Faith, because everything is connected with the Reason of everything.

These parents know exactly what they are doing. Here is Karen Edmisten: "Most of us would probably agree that in many areas of our society specialization can and does lead to fragmentation. Parsing education into subjects, which are then studied in a vacuum apart from other subjects, can also lead to a fragmented understanding of both the subjects and the world around us." Contrast the method or "unmethod" described in action here, in which history is full of literature, literature marches through history, history is interlaced with science, and everything points to Faith, because everything is connected with the Reason of everything.

There is in fact a deep compatibility between the radical homeschool or unschooling approach to education and other manifestations of the Catholic understanding of human nature. Natural Family Planning, like unschooling, is regarded by many as an impractical ideal or an ideology, but when practised in the right spirit it reveals itself as something else entirely. The point about NFP is that it requires mutual respect and attentiveness to the whole person of the spouse. It should not be treated as just another instrument for achieving the aim of reducing fertility. For a couple to master NFP is to for them to grow in mutual love and knowledge. Similarly, unschooling is based on respect for the child and love between generations.

And yet the accounts in the book underline one important fact. It seems that, to be realistic, one must acknowledge that the success or failure of the unschooling as well as the homeschooling approach depends in large part not just on the individual child and his motivation, but on the family as a whole, especially the parents. The flourishing of any individual requires the right kind of attention from others. Precisely because unschooling is a spirituality, it will only succeed (on almost any measure of success) if the family is of a certain type or has a certain maturity. As Cindy Kelly says in her chapter, “The most powerful way to encourage my sons to enjoy a new area of learning is to model it myself and continue our dialogue about their interests and mine.” Not every parent is capable of that; not all have the leisure, confidence, or motivation to do so. But for those who do, I can imagine - after reading this book - that it might work beautifully well.

And yet the accounts in the book underline one important fact. It seems that, to be realistic, one must acknowledge that the success or failure of the unschooling as well as the homeschooling approach depends in large part not just on the individual child and his motivation, but on the family as a whole, especially the parents. The flourishing of any individual requires the right kind of attention from others. Precisely because unschooling is a spirituality, it will only succeed (on almost any measure of success) if the family is of a certain type or has a certain maturity. As Cindy Kelly says in her chapter, “The most powerful way to encourage my sons to enjoy a new area of learning is to model it myself and continue our dialogue about their interests and mine.” Not every parent is capable of that; not all have the leisure, confidence, or motivation to do so. But for those who do, I can imagine - after reading this book - that it might work beautifully well.

Tuesday, 16 August 2011

Back to the Circle

Reviewers of Beauty for Truth's Sake have been kind, but even the most ecstatic would admit that there are weak and even silly patches in the book, especially in the chapter called "The Golden Circle", where I play with some ideas relating theology and mathematics (inspired by Simone Weil's work and Vance Morgan's excellent book on her). Apart from anything else, I came up with a concept called "the Golden Circle" and wasn't able to develop it properly, since I lack the mathematical ability to do so. The "Circle" was simply a Golden Rectangle inscribed in a circle, which I thought one could use to explore the relations of Pi to Phi (Φ and π are connected together by the fact that the Golden Rectangle’s diagonal forms the diameter of the circle).

But my conception of the Golden Circle has evolved, and Michael Schneider has kindly redrawn it for me on the right (an intermediate stage was discussed in an earlier post). The Golden Circle itself is now a Golden Ring, shown in yellow. There are in fact three circles, one inscribed within the short sides of a Golden Rectangle, one inside the long sides, and one through the corners of the rectangle. On the basis of Pythagoras's Theorem, a large number of relationships can be established between areas and lengths in this figure, since we know that the circumference of a circle is Pi multiplied by the diameter, and the area is Pi multiplied by the radius squared. For example, the circumference of the middle-sized circle (the outside of the yellow ring) is Pi times Phi. But I'll leave you to work out what the rest of them are. Let me know sometime. It might make a nice exercise for a geometry class. The theology can wait.

But my conception of the Golden Circle has evolved, and Michael Schneider has kindly redrawn it for me on the right (an intermediate stage was discussed in an earlier post). The Golden Circle itself is now a Golden Ring, shown in yellow. There are in fact three circles, one inscribed within the short sides of a Golden Rectangle, one inside the long sides, and one through the corners of the rectangle. On the basis of Pythagoras's Theorem, a large number of relationships can be established between areas and lengths in this figure, since we know that the circumference of a circle is Pi multiplied by the diameter, and the area is Pi multiplied by the radius squared. For example, the circumference of the middle-sized circle (the outside of the yellow ring) is Pi times Phi. But I'll leave you to work out what the rest of them are. Let me know sometime. It might make a nice exercise for a geometry class. The theology can wait.

Thursday, 11 August 2011

Great Books and Western Studies

What is a "great book"? It is surely a book that stands re-reading many times, and deserves to be so read. And an educated person is one who knows the great books, and re-reads them. C.S. Lewis is quoted in Walter Hooper's Foreword to C.S. Lewis's Lost Aeneid (a wonderful new parallel text from Yale that could be used to teach Latin translation as well as introduce the Aeneid), as follows:

There is no clearer distinction between the literary and the unliterary. It is infallible. The literary man re-reads, other men simply read. A novel once read is to them like yesterday's newspaper. One may have some hopes for a man who has never read the Odyssy, or Malory, or Boswell, or Pickwick; but none (as regards literature) of the man who tells us he has read them, and thinks that settles the matter. It is as if a man said he had once washed, or once slept, or once kissed his wife, or once gone for a walk.I feel better, now, about having read The Lord of the Rings so many times. Reading great books, however (even more than one), does not suffice to make a person educated. They need to be placed in a context, they need to be loved, and they need to open the door to other interests and other

Tuesday, 9 August 2011

Diagram of the cosmos

The Cosmati Pavement in Westminster Abbey was underfoot when the Pope met the Archbishop of Canterbury in 2010, and when William married Kate in 2011. It is the traditional site of royal coronations -- 38 kings and queens have been crowned on this spot since 1268 (the symbolism of the ceremony is analysed by Aidan Nichols OP in his book The Realm). The Pavement is a kind of Western "mandala", a representation of the entire cosmos based on squares and circles and sacred numbers. I have posted about it before, but there are things to add. For one thing a much more detailed image of the entire Pavement is available here, on the Getty web-site.

The central disk of onyx represents the world, and the two sets of four roundels around it the four elements and four qualities unified by love, a symbol of the Great Chain of Being that bound the monarch to the lowliest subject and the highest angel under God, as in this fifteenth-century text:

The central disk of onyx represents the world, and the two sets of four roundels around it the four elements and four qualities unified by love, a symbol of the Great Chain of Being that bound the monarch to the lowliest subject and the highest angel under God, as in this fifteenth-century text:

"In this order, hot things are in harmony with cold, dry with moist, heavy with light, great with little, high with low. In this order, angel is set over angel, rank upon rank in the kingdom of heaven; man is set over man, beast over beast, bird over bird and fish over fish, on the earth, in the air and in the sea: so that there is no worm that crawls upon the ground, no bird that flies on high, no fish that swims in the depths, which the chain of this order does not bind in the most harmonious concord. Hell alone, inhabited by none but sinners, asserts its claim to escape the embraces of this order." (Sir John Fortescue, trans. On Nature, 1492.)There was a Latin inscription to accompany the Pavement which described the age of the world from beginning to end as 19,683 years - the lifespan of the macrocosm conceived as a living creature. However inaccurate this is in terms of modern cosmology, it was an attempt to make the Pavement an image of the whole of space-time. We lost our "Theory of Everything", and modern science has been trying to get it back ever since.

Thursday, 4 August 2011

Post-secularism

C. John Sommerville's book is a brilliant indictment of the modern university. He writes about it in an article published in Reconsiderations, available online. As he says there, "Secularism is an impoverishment of thought. Religion can be a way of opening our minds, and quite relevant to intellectual questions," adding:

To be clear, accommodating Christian and other religious voices would not make universities Christian. They would remain secular in the sense of being neutral. Religion wouldn’t rule. But it need not be ruled out. Universities wouldn’t be officially Christian unless they somehow privileged Christian viewpoints. That would not be good even for those Christian viewpoints. We need to keep them honest, and you do that by leaving them open to discussion.This seems to be a good example of the right kind of "post-secularism" -- what many Catholic thinkers these days are calling "a new secularity" genuinely open to truth, unlike the "liberalism" wrongly so called, which closes the mind in advance by operating with a narrow conception of both reason and freedom.

Friday, 29 July 2011

Communio - an introduction

One of the great resources of modern Catholic thought is the international review Communio, edited in the English language by David L. Schindler. Founded in the wake of the Second Vatican Council by Hans Urs von Balthasar and Josef Ratzinger with Henri de Lubac SJ and Louis Bouyer, with the support of Karol Wojtyla in Poland (later John Paul II), it has never sold in huge numbers but has had and is having a huge if indirect impact on the Catholic Church through the fact that many of its contributors and editors have been appointed bishops and cardinals, often placed in key positions (Francis George, Marc Ouellet, Christoph Schonborn, Angelo Scola, and of course Ratzinger himself are the most obvious). Communio theology is an expression of the Catholic ressourcement or "back to the sources" movement that partly influenced the liturgical movement and the Second Vatican Council, and is certainly now influencing their interpretation and consolidation under Pope Benedict.

All around the United States there are Communio circles that meet to discuss articles from recent issues, but in the UK there seem to be too few subscribers in any one place to make this viable. Even in the States, many readers find Communio hard going. (Second Spring was founded, in part, to offer a more accessible way into this tradition of Catholic thought.) But if you are seriously interested in creatively orthodox Catholic thought, Communio is indispensable. The journal has a News page which is a good place to start, and this has links to a number of articles.

I have selected several important Communio articles for our own site, which you can find under author in our Articles section linked from the menu at Second Spring. Look for example under Bouyer, Crawford, Granados, Hanby, Henrici, Kaveny, Lopez, Melina, Nault, Olsen, Ouellet, Schindler (D.L.), Schindler (D.C.), Schonborn, Scola, Sicari - as well as, of course, Popes Benedict and John Paul II. There are also several recent ones on Catholic social teaching to be found in the articles section of our "Economy" site - Abela, Berry, Cloutier, Healy, Schindler (both), and Walker. And for an introduction to Balthasar go here. I hope to write more about Communio and education in the future.

All around the United States there are Communio circles that meet to discuss articles from recent issues, but in the UK there seem to be too few subscribers in any one place to make this viable. Even in the States, many readers find Communio hard going. (Second Spring was founded, in part, to offer a more accessible way into this tradition of Catholic thought.) But if you are seriously interested in creatively orthodox Catholic thought, Communio is indispensable. The journal has a News page which is a good place to start, and this has links to a number of articles.

I have selected several important Communio articles for our own site, which you can find under author in our Articles section linked from the menu at Second Spring. Look for example under Bouyer, Crawford, Granados, Hanby, Henrici, Kaveny, Lopez, Melina, Nault, Olsen, Ouellet, Schindler (D.L.), Schindler (D.C.), Schonborn, Scola, Sicari - as well as, of course, Popes Benedict and John Paul II. There are also several recent ones on Catholic social teaching to be found in the articles section of our "Economy" site - Abela, Berry, Cloutier, Healy, Schindler (both), and Walker. And for an introduction to Balthasar go here. I hope to write more about Communio and education in the future.

Tuesday, 12 July 2011

Tolkien - some thoughts

Here are some thoughts on the possible use of The Lord of the Rings by homeschoolers.

The first thing is not to impose the book as a lesson, but introduce it naturally at an early stage. Reading to a child every day, for example as part of a bed-time ritual that can start as soon as the child is capable of gazing at a picture, is the foundation of everything. (You know this already.) In the case of Tolkien, there are books that can be used much earlier than LoR – his Father Christmas Letters, Smith of Wootton Major, and of course The Hobbit – as well as dozens of books by other authors that can be read in conjunction with these, books by the other Inklings, traditional folklore from all over the world, and of course many wonderful passages from the Bible. It doesn’t matter that one is reading a book where the vocabulary is difficult – the meaning of a word can often be gleaned from context, although you should encourage questions and have a dictionary to hand.

When it comes to LoR, reading aloud continues to be important long after the child can read for himself. The sound of the words is important. Spend a bit of time getting the pronunciation of the Elvish words right (the Appendices contain some guidance) – something I never did. The magic is in the language, as Tolkien would be the first to tell you.

Once the story itself has come alive in the child’s imagination, and perhaps after it has been read more than once, it becomes possible to explore a range of topics suggested by the book. Let’s consider Language, Philosophy, Religion, Nature, Geography, History, Mythology, and Art.

The first thing is not to impose the book as a lesson, but introduce it naturally at an early stage. Reading to a child every day, for example as part of a bed-time ritual that can start as soon as the child is capable of gazing at a picture, is the foundation of everything. (You know this already.) In the case of Tolkien, there are books that can be used much earlier than LoR – his Father Christmas Letters, Smith of Wootton Major, and of course The Hobbit – as well as dozens of books by other authors that can be read in conjunction with these, books by the other Inklings, traditional folklore from all over the world, and of course many wonderful passages from the Bible. It doesn’t matter that one is reading a book where the vocabulary is difficult – the meaning of a word can often be gleaned from context, although you should encourage questions and have a dictionary to hand.

When it comes to LoR, reading aloud continues to be important long after the child can read for himself. The sound of the words is important. Spend a bit of time getting the pronunciation of the Elvish words right (the Appendices contain some guidance) – something I never did. The magic is in the language, as Tolkien would be the first to tell you.

Once the story itself has come alive in the child’s imagination, and perhaps after it has been read more than once, it becomes possible to explore a range of topics suggested by the book. Let’s consider Language, Philosophy, Religion, Nature, Geography, History, Mythology, and Art.

Friday, 3 June 2011

The Lord of the Rings for homeschoolers

At a recent Tolkien-related event in Italy I was speaking about the theme of "friendship" in The Lord of the Rings. In a way it is could be called a central theme, since the story is all about a Fellowship. Of course the novel is about many other things as well. Tolkien himself said it was about Death and Immortality, and on another occasion that it was about "the ennoblement of the humble" (e.g. Sam Gamgee and the Hobbits). But it is also about Marriage, Myth and reality, Heroism and Virtue, Temptation and Freedom, Power (true and false), Beauty, Technology, Nature, Creativity, Social Order, the Fall, and Language.... The novel could also be used quite naturally by home-schoolers to get children interested in and thinking about Geography, History, Ethics, Politics, Language, Poetry, Natural History, Mythology, and Philosophy. Is anyone interested in hearing more about this idea?

Monday, 25 April 2011

New Evangelization through Drama

|

| The Quality of Mercy |

Philosophy is unavoidable, of course. As Chesterton long ago noted, everyone is a philosopher; whether you unconsciously absorb your philosophy from somewhere else (such as the newspapers) or think it through for yourself. And how you think about things shapes the way you act and behave, so nothing is richer in practical implications (even for art). Do you believe in God? But what kind of “God” is being talked about? What does the word mean to you? I have tried to address that question online here, and the main Second Spring web-site contains many useful articles on philosophical topics. Nevertheless, philosophy is never going to be a very effective means of evangelization. People open their minds, or change them, for other reasons than a good argument. “Heart speaks unto heart”, not head unto head, as Newman realized. The Christian faith places us under an obligation to communicate it where possible. But effective communication involves the imagination and the spirit, not just the reason or the intelligence.

Just as we cannot separate the virtues of faith, hope, and love, so we cannot separate truth, goodness, and beauty. It is the heart where they join together. The way we live and the beauty we produce are the most eloquent expression of the truth we believe. You cannot communicate a truth that has not changed you, and we are changed only by a truth that we recognize as in some way beautiful.

Sunday, 27 March 2011

Paying attention

Attention to the child is the key to the teacher’s success, and the child’s own quality of attention is the key to the learning process, or so Simone Weil asserts in her essay “Reflections of the Right Use of School Studies”. She almost goes as far as to say that the subject studied and its contents are irrelevant; the important thing, the real goal of study, is the “development of attention”. And why? Because “prayer consists of attention”, and all worldly study is really a stretching of the soul towards prayer.

“Never in any case whatever is a genuine effort of the attention wasted. It always has its effect on the spiritual plane and in consequence on the lower one of the intelligence, for all spiritual light lightens the mind.” An attempt to grasp one truth – even if it fails – will assist us in grasping another. “The useless efforts made by the Cure d’Ars, for long and painful years, in his attempt to learn Latin bore fruit in the marvellous discernment that enabled him to see the very soul of his penitents behind their words and even their silences.”

“Never in any case whatever is a genuine effort of the attention wasted. It always has its effect on the spiritual plane and in consequence on the lower one of the intelligence, for all spiritual light lightens the mind.” An attempt to grasp one truth – even if it fails – will assist us in grasping another. “The useless efforts made by the Cure d’Ars, for long and painful years, in his attempt to learn Latin bore fruit in the marvellous discernment that enabled him to see the very soul of his penitents behind their words and even their silences.”

Attention is desire; it is the desire for light, for truth, for understanding, for possession. It follows, according to Weil, that the intelligence “grows and bears fruit in joy”, and that the promise or anticipation of joy is what arouses the effort of attention: it is what makes students of us.

Thursday, 24 February 2011

Newman on Higher Education

When Archbishop Cullen appointed Newman as Rector of the proposed Catholic University of Ireland in 1851, it was to spearhead the Church’s response to a scheme designed to enable Catholics to obtain degrees within the secular, utilitarian system devised by Sir Robert Peel: the Queen’s Colleges of Belfast, Cork and Galway. As Newman wrote, the University was intended to attract American as well as Irish students, and to become a centre of Catholic cultural renewal for the whole English-speaking world, “with Great Britain, Malta (perhaps Turkey or Egypt), and India on one side of it, and North America and Australia on the other.” It was an extraordinary vision, and even if this first Irish Catholic university was reabsorbed by the secular system after Newman’s departure, it had provided the occasion for a series of discourses on education (The Idea of a University) which continue to influence Catholic thinking today. John Paul II’s Ex Corde Ecclesiae (1990), defining the basic constitution of a modern Catholic university, clearly bears the mark of Newman’s thought.

Today, Newman’s ideas are more urgent and relevant than ever. Zenit has recently published a useful series of articles on this theme by Fr Juan R. Velez ("Newman's 'Idea' for Catholic Higher Education", Part 1, Part 2). The tensions between “liberal” or progressive and “conservative” or authoritarian elements in the Catholic academic world tend to come to a head over the

Wednesday, 16 February 2011

Fractals

Fractals are infinitely complex and beautiful patterns produced through the repetition of a simple formula or shape, patterns which often appear rough or chaotic and which can be found everywhere in nature (the surface of the sea, the edge of a cloud, the dancing flames in a wood fire). I have written about them briefly before.

Fractals are infinitely complex and beautiful patterns produced through the repetition of a simple formula or shape, patterns which often appear rough or chaotic and which can be found everywhere in nature (the surface of the sea, the edge of a cloud, the dancing flames in a wood fire). I have written about them briefly before.What appeals to us in such patterns, perhaps, is the combination of simplicity and complexity. They allow our minds scope to expand, and our imaginations to take off in the direction of the infinite, but at the same time to rest in a unity. It is similar to the reason we love science. Scientists are seeking the simple secret at the heart of the complex - the formula or combination of universal laws that governs all of reality and explains why it works or appears the way it does.

Something similar is happening in art, when the artist seeks unity of concept or meaning or mood in a complex scene or sight or landscape.

Not all beauty is produced by these "recursive algorithms" or the repetition of self-similarity at different scales of magnitude. Sometimes a pattern is just there in the thing and does not repeat itself. But beauty always has something to do with order, which means the finding of a unity of form in something complex - a balance between the Many and the One. The finding of unity gives us joy (which is why we call it beautiful) because it enables us to recognise the Self in the Other, outside ourselves. It causes us to expand our boundaries to include the other thing as grasped and understood, or at least as situated in a relationship to us. Fractal patterns are a version of that experience. We sense the unity, but because it is expressing itself as never-ending complexity, it never gets boring.

Therefore all beauty, including fractal beauty, reminds us of God, who is both infinitely simple (in himself, as pure love) and yet infinitely complex (in what he contains and creates).

Tuesday, 15 February 2011

Child-centred education: 3

We all know there is a child still within us. That child has many aspects. It is ignorant, selfish, immature, confused. It may be desperately in need of love it has never received. But it is innocent and pure. I think it was in that sense that Georges Bernanos wrote, “What does my life matter? I just want it to be faithful, to the end, to the child I used to be.”

Christianity has given a particular importance to childhood. It certainly transformed, over time, the way children were perceived in classical civilizations. From the statement of Christ, “Whoever does not receive the kingdom of God like a child shall not enter it” (Mk 10:15), it followed that there was something valuable and to be imitated in the state of childhood. Normally children are told to grow up and become like adults, not the other way around. Childhood is an undeveloped stage, but in some ways it also represents a more perfect state, in which we

Christianity has given a particular importance to childhood. It certainly transformed, over time, the way children were perceived in classical civilizations. From the statement of Christ, “Whoever does not receive the kingdom of God like a child shall not enter it” (Mk 10:15), it followed that there was something valuable and to be imitated in the state of childhood. Normally children are told to grow up and become like adults, not the other way around. Childhood is an undeveloped stage, but in some ways it also represents a more perfect state, in which we

Wednesday, 9 February 2011

Child-centred education: 2

More notes from a work in progress.

Another great figure in child-centred education is Rudolf Steiner (d. 1925), the founder of a school of spiritual philosophy called Anthroposophy and the inspiration for around 1000 Waldorf Schools around the world, including this one in Edinburgh. The schools began in 1919 when Steiner was invited to create one for the children of workers at the Waldorf-Astoria cigarette factory, based on the ideas in his 1909 book, The Education of the Child. Steiner believed in the need to educate with the spiritual as well as emotional, cultural and physical needs of children in mind, and believed that they progress through a series of developmental stages corresponding to the evolution of human consciousness itself. Abstract and conceptual thinking develops late, around the age of 14, and so the early years are more focused on art, the

Another great figure in child-centred education is Rudolf Steiner (d. 1925), the founder of a school of spiritual philosophy called Anthroposophy and the inspiration for around 1000 Waldorf Schools around the world, including this one in Edinburgh. The schools began in 1919 when Steiner was invited to create one for the children of workers at the Waldorf-Astoria cigarette factory, based on the ideas in his 1909 book, The Education of the Child. Steiner believed in the need to educate with the spiritual as well as emotional, cultural and physical needs of children in mind, and believed that they progress through a series of developmental stages corresponding to the evolution of human consciousness itself. Abstract and conceptual thinking develops late, around the age of 14, and so the early years are more focused on art, the

Thursday, 3 February 2011

Child-centred education: 1

Notes from a work in progress.

Insight into the true value of the child can be traced back to Christ, though it has to be said it remained mainly implicit during most of the succeeding centuries, and before the eighteenth century childhood was often considered merely a stage of weakness and immaturity to be got through as quickly as possible. We'll come back to the child later in this series. The modern period saw a transformation of educational theory and practice. In the wake of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (d. 1778) and the Romantics, most developments reflect a greater respect for the nature and natural development of the child. Rousseau himself – not a great educator, but a considerable influence through his novel Emile – believed in the natural goodness and value of the child,

Sunday, 23 January 2011

Beyond Physics

The relationship between physics and metaphysics (literally "beyond physics") is a fascinating one. It helps sometimes to remember that we can approach God from the side of philosophy and not just on the basis of revelation. Terry Pratchett, the English fantasy writer who has sold more than 60 million books and once said he was "rather angry with God for not existing", in a more recent interview ventured the view that "It is just possible that once you have got past all the gods that we have created with big beards and many human traits, just beyond all that, on the other side of physics, they [the gods] just may be the ordered structure from which everything flows." Indeed, the Christian idea of God, properly understood, is of something that could not not exist, if the world is to make any kind of sense.

Ever since 2006 in Regensburg, Pope Benedict XVI has spoken about the need for "broadening our concept of reason and its application". But what

Ever since 2006 in Regensburg, Pope Benedict XVI has spoken about the need for "broadening our concept of reason and its application". But what

Saturday, 15 January 2011

Music unforgotten

Listeners to Radio Three had a treat over Christmas. The BBC devoted twelve solid days and nights to playing everything composed by Mozart. What struck me is how, where Beethoven comes over as emotional, heroic and tragic, and Bach as mathematical, angelical and lyrical, Mozart often seems simply “playful”. But this may be connected with the reason his music is so profound. It resembles nature, in the sense of natura naturans (“nature naturing”, or doing what nature does). In nature, creative freedom always manifests a law – but the deepest law of all is the pure ebullient spontaneity of the Good.

John Tavener said of Mozart (in the programme notes for Kaleidoscopes in 2005):

I have always regarded Mozart as the most sacred and also the most inexplicable of all composers. Sacred, because more than any other composer that I know, he celebrates the act of Being; inexplicable, because the music contains a rapturous beauty and a childlike wonder that can only be compared to Hindu and Persian miniatures, or Coptic ikons.

In an essay in the Winter 2006 issue of Communio, Fr Jonah Lynch sees in Mozart a kind of Catholic balance that reflects the paradox of the Incarnation:

Mozart’s melodies carry something of the birth of an infant God, the remarkable union of opposite absolutes, total simplicity and infinite depth. Only here is the completely free and ever-surprising united to formal structural perfection.

The work of Mozart and the other great composers echoes the “unforgotten music” that we carry in our bones. It opens our senses, so that we feel the air of Paradise – what Josef Pieper in Only the Lover Sings calls the “paradise of uncorrupted spiritual forms” – and notice the fragrance that still clings to our coats of skin. Perhaps it is not too much to suggest that when we hear this music, even if like the Good Thief we are still hanging on the cross, we become more conscious of the possibility of grace.

Saturday, 8 January 2011

Constructing the Universe Classroom

Monday, 3 January 2011

Natural selection

A couple of times in this blog I have commented on the theory of evolution and promised to come back to it. Though I did not address it directly in my book, it is one of the big influences on modern education (along with Freud, who deserves separate treatment). But the influence is not so much from the science of evolution as from the "idea", often exaggerated into an ideology that purports to explain everything. One of the most informative and enjoyable presentations of the current state of knowledge and speculation is Nick Lane's Life Ascending: The Ten Great Inventions of Evolution. The "inventions" in question are life itself, DNA, photosynthesis, the complex cell, sex, movement, sight, hot blood, consciousness and death. In each case, science is trying to show how these breakthroughs were achieved without intelligent design, by physiochemical processes over long stretches of time. Though many of the answers remain elusive, the search for them has thrown up a huge amount of fascinating information. In this sense the book is a treasure trove. Lane concludes that the "convergence of evidence" from many fields makes it impossible seriously to doubt that life did evolve. Whether this is compatible with faith in God is a question he sensibly leaves open. That is something I debated with Clive Copus in the Catholic Herald last year. Readers interested in this question would do well to look at writings by Simon Conway Morris and Conor Cunningham. You will also find a number of relevant articles on the main Second Spring site, if you look in the online Articles section under Caldecott, Case, Dulles, Fedoryka, Hanby ("Saving the Appearances"), Olsen and Schonborn.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)